Move fast and save things

This is the third chapter in my five-year retrospective. After the life of Pabio, where we somehow convinced Y Combinator that sofas were SaaS and built an apartment in Zurich’s main train station, we were about to discover that math doesn’t care about your YC badge.

Our culture was… unique? Carlo introduced the XX:59 meeting - every meeting started at 29 or 59 minutes past the hour so if you’re on time at 8 am, you’re already late. Miss the 7:59 am standup by even 30 seconds? You’re out, read the notes later. On Saturday, we were nice enough to let everyone sleep in and have the standup at 9:59 am instead, 996-ing before it was cool.

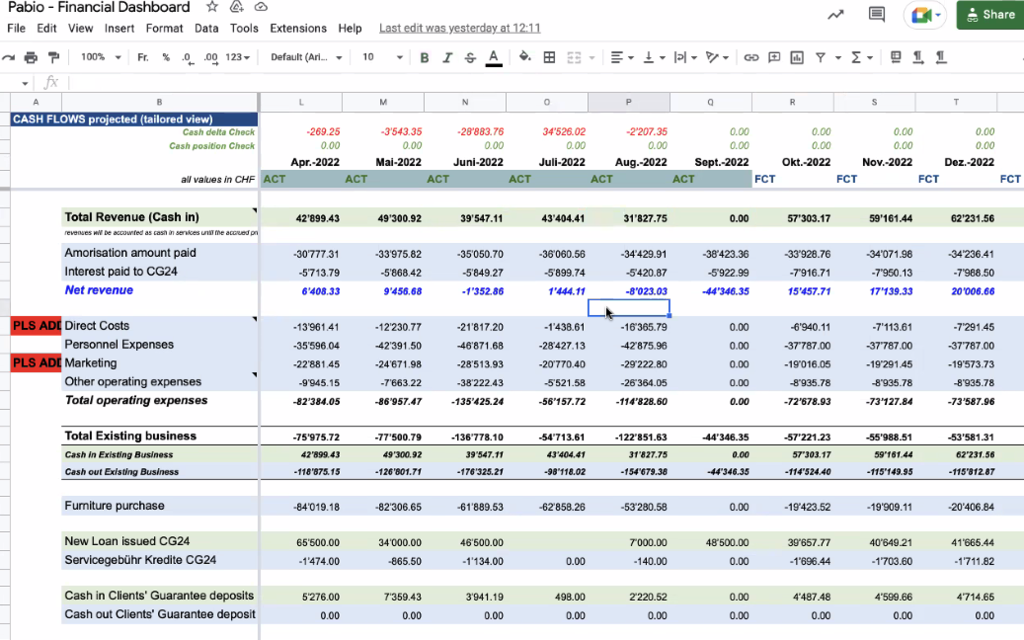

In the second half of 2022, from the outside it looked like it was all starting to work. We had over $700,000 ARR, 200+ subscriptions, and 15-20% monthly growth - a recipe for great investor updates. But behind the scenes, it was a mess.

Our accountability system was elegant to the point of absurdity: quarterly OKRs became weekly MITs (Most Important Tasks), which became daily MITs, which became hourly panic. Every morning’s standup started with declaring if you were “On track” or “Fucked up”. By month six, “Fucked up” had become our default state of being, and we’d only elaborate if we were actually on track.

For example, we accepted bank transfers because some Swiss customers didn’t want to enter their credit card details, but what we got was a daily game of “guess which customer this random CHF 347.23 payment belongs to”. Some customers would pay CHF 299 instead of CHF 300 because, I don’t know, they disliked round numbers? Our reporting became creative fiction and Monique had to moonlight as our part-time CFO.

The Frankenstein monster we called our financial stack - Lounge (internal ERP) talking to Stripe (payment gateway) talking to Bexio (accounting tool) would randomly decide to take vacation days and Monique and I would have to manually reconcile the accounts.

Accidental discovery

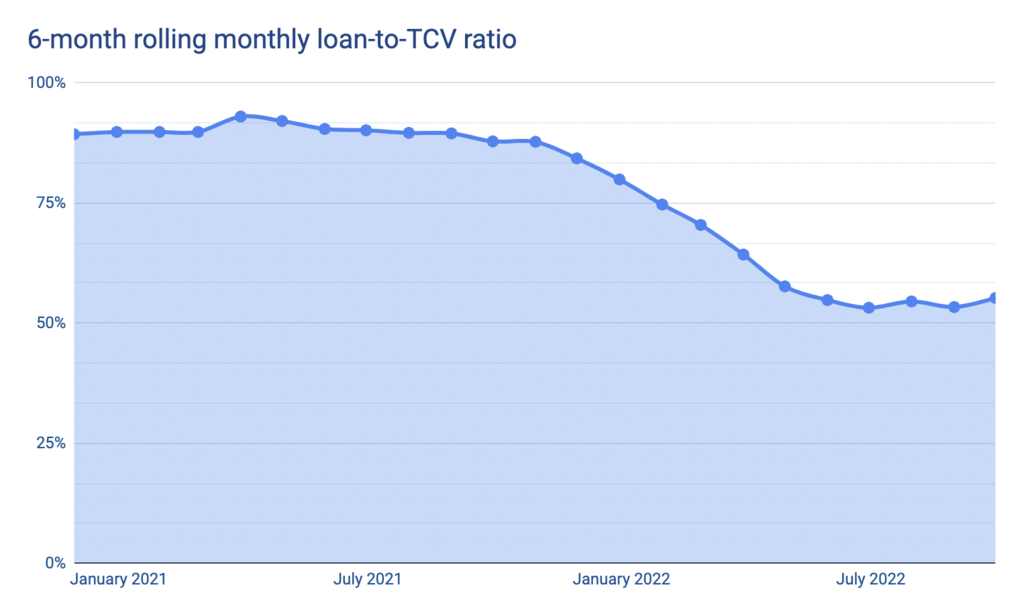

Our debt financing provider had been slow with payments for a few months already, but we’d gotten used to their delays. So I was building yet another KPI dashboard (because if you can’t fix your business, at least make pretty charts about it) when I created a graph of the loan we’d get to purchase the furniture compared to the value of the contract. To my shock, the line went down. Like ski-slope-in-the-Alps down.

Carlo and I had one of those Zoom calls where you just stare at each other in silence for a solid minute. Turns out our debt financing provider had been giving us less and less credit per order, meaning that we end up spending more on furniture than we got in the first place. We’d been losing money on every single apartment, for months, and we had no idea.

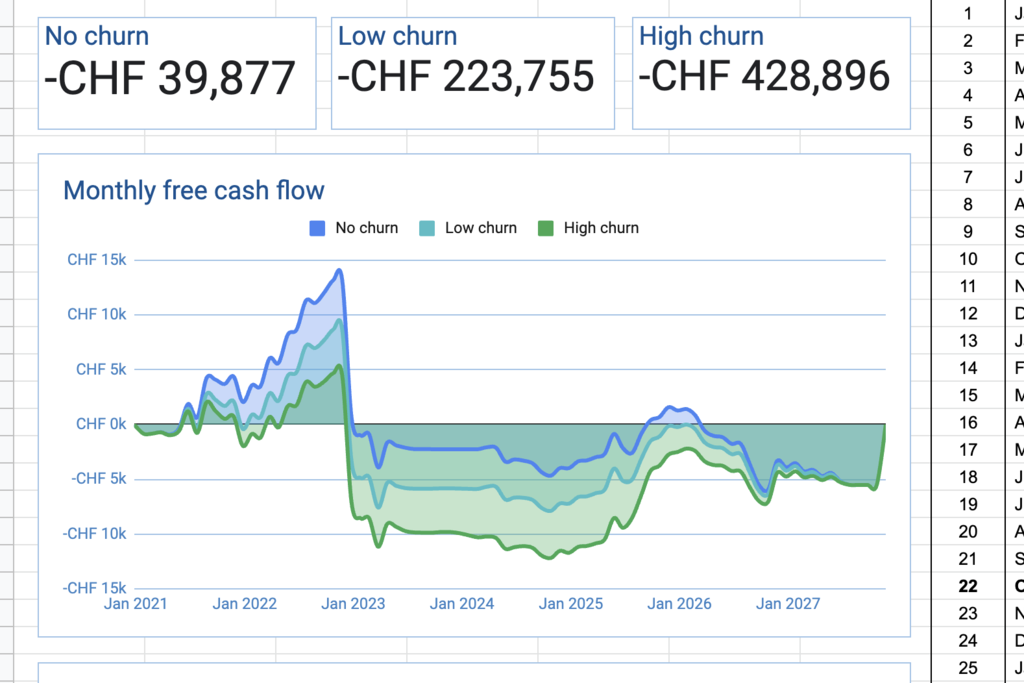

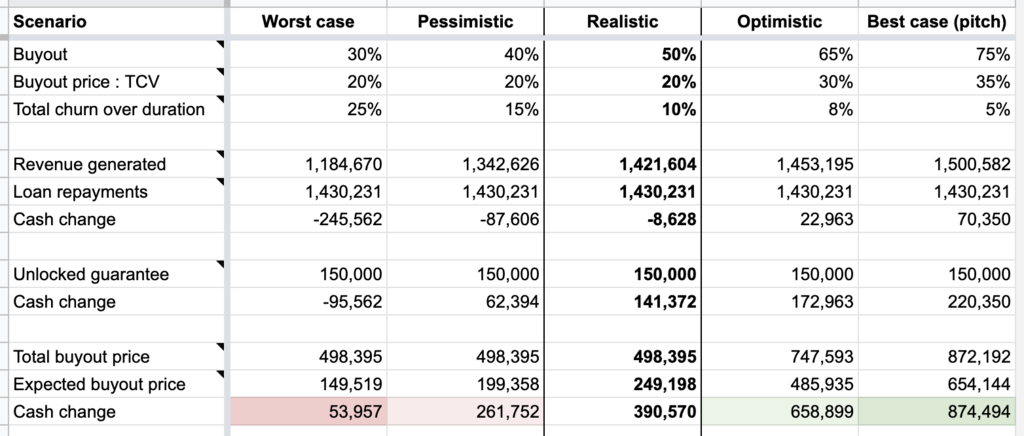

Carlo went into full forensic accountant mode and built a comprehensive P&L that included all the inconvenient realities we’d been ignoring. Turns out our “30-40% gross margins” assumed we lived in a fantasy world where customers kept paying forever instead of ghosting us after the first year and we were never spending more on buying furniture and organizing deliveries than we were receiving in factoring.

We redid the unit economics to calculate updated pricing for each apartment. A customer who’d been discussing his proposal for weeks, watched his monthly payment go from CHF 450 to CHF 760 while we were on the phone with him, which clearly was not going to work. Since the interest rates were going up and we couldn’t significantly raise prices, we were already losing money on every apartment.

The truth hit like a freight train carrying all our damaged furniture: subscription furniture in Europe was fundamentally a zero interest rate phenomenon.

We called our debt financing provider and they told us: “We can’t finance any more deals, the political situation in Europe… rising interest rates… we’re stopping all new loans effective immediately”.

We had a quarter million in outstanding loans pending for the last few months, which was supposed to arrive any day. Instead, we got radio silence. The business model we’d spent two years building - where a debt partner fronts the furniture cash and we collect monthly subscriptions - had just evaporated in a five-minute phone call.

Wartime CEO mode

The moment we discovered we were basically a charity for Swiss people who wanted nice furniture, Carlo went full “wartime CEO” mode. The guy who used to debate font choices for hours now made decisions in seconds. “Can we survive without this for 30 days?” If yes, cut it. “Will this directly generate cash?” If no, kill it. Within days of our realization, we stopped all marketing spend, stopped taking new orders, and only spent money on things that were absolutely necessary.

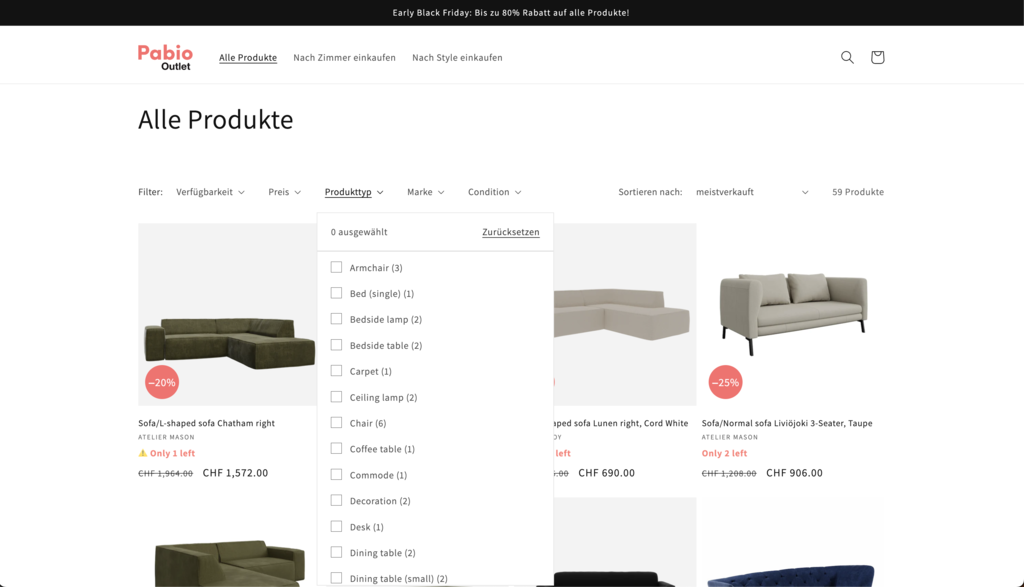

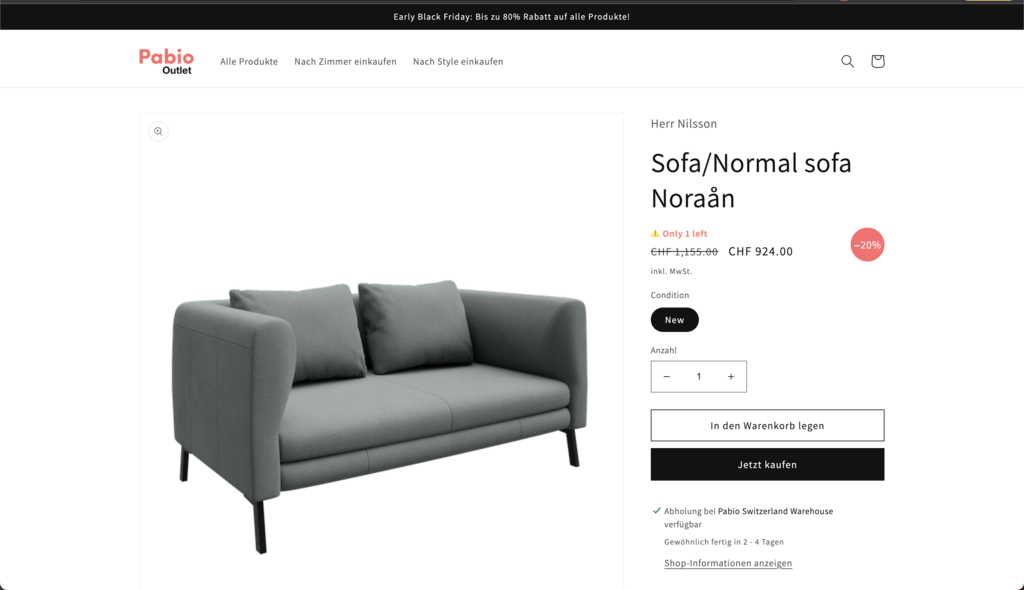

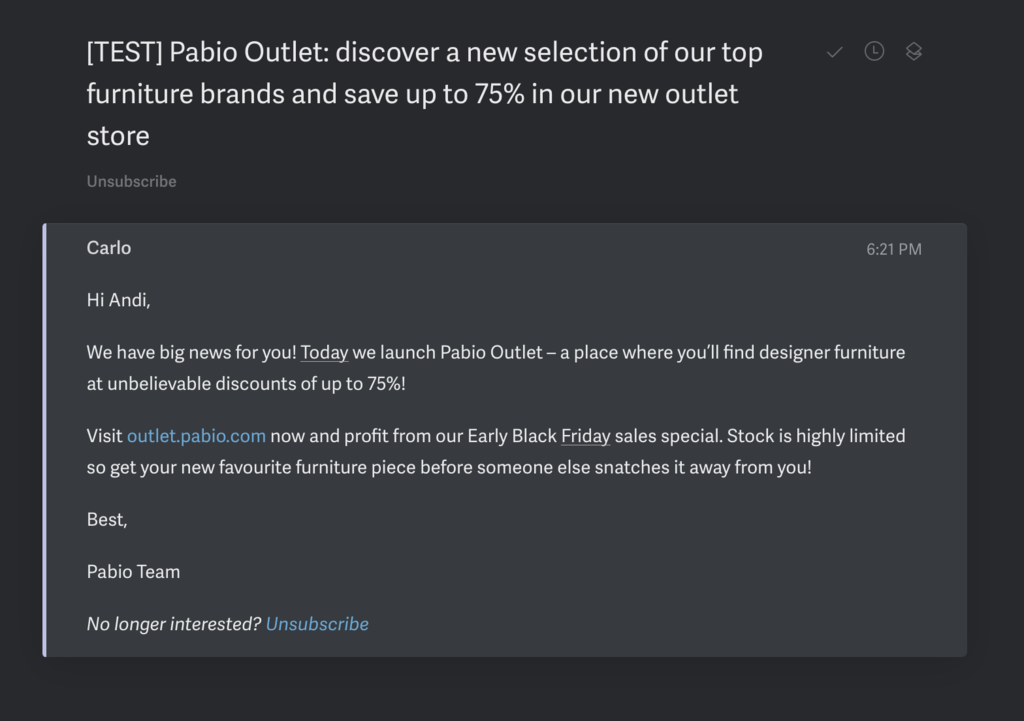

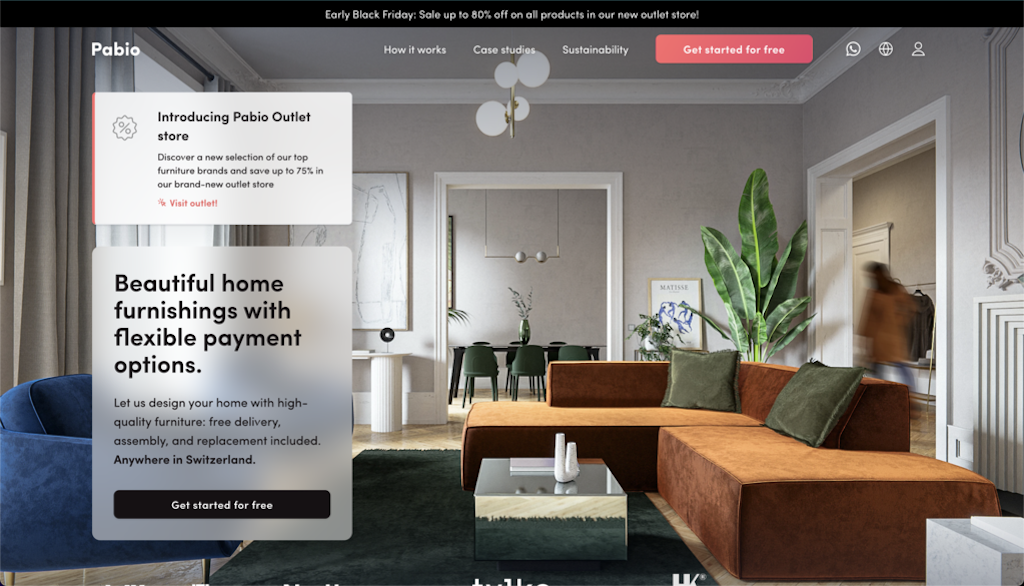

Our solution to having a warehouse full of furniture and no cash was magnificently simple: sell everything at fire-sale prices. Within 72 hours of realizing everything had to go, we launched an Outlet Store. I built it on Shopify in a weekend-long coding marathon fueled by energy drinks and existential dread.

Of course, nothing worked properly the first time around. A pricing bug set everything to CHF 0, and we had to cancel a dozen “free” orders from confused customers who thought we were doing a Black Friday giveaway in November. When we finally got prices working, payments broke. We ended up taking some orders via WhatsApp and PayPal like it was 2005.

The whole team became salespeople overnight. Neel created WhatsApp scripts and outbound templates. Carlo negotiated with anyone who’d listen. We sold furniture to ex-employees, random people from Facebook Marketplace, and I think someone’s grandmother. By December, the warehouse was empty. We’d turned hundreds of thousands in designer furniture into thousands in cash. The math was painful, but the alternative was paying more in warehouse rent on furniture nobody wanted.

Carlo worked hard over the next weeks and months to secure alternate financing, but because of the rising interest rates other financial institutions didn’t want to risk it either.

We had some cash left, so we had two options: we could either return the money to our investors, or we could pivot. We spoke to our lead investors who told us that no investor would want a 0.1x return, and they invested in us as a team in the first place, so we should pivot. Carlo and I, now knowing that this business model was fundamentally flawed, decided that we will work on something completely different. And that means we had to let everyone go.

We scheduled hour-long calls with each team member individually, and over the course of a single very long day, we told everyone that we had to let them go because we were shutting down the existing business and will start thinking of something new to work on. This was one of the worst days of my life. It was really hard to say goodbye to everyone, but it had to be done.

The Zurich warehouse stands empty now, probably being used for something sensible like storing things that people actually want. But here’s the thing: for two and a half glorious, chaotic years, we helped hundreds of people create homes they loved. We made beautiful spaces accessible. Yes, we learned lessons that are priceless, but it costed millions.

The acquisition that wasn’t

In January 2023, we started approaching potential buyers for what was left of our assets. A German company, a part of one of the world’s largest players in this space, wanted to buy everything - the brand, website, customer contracts, maybe even our Lounge system. It was not exactly the exit we’d dreamed of, but when you’re drowning, you don’t negotiate the color of the life preserver.

The due diligence dragged on for months, but luckily we had already validated our next idea and were working on that in parallel. The new buyers wanted every contract, every invoice, every Excel sheet we’d ever created. Carlo and I spent entire days exporting data, creating summaries, and answering questions about German VAT implications. By March, we had a signed Letter of Intent. By April, we had a signed purchase agreement. We even started planning the PR announcement, thinking we were going to make it sound like a strategic acquisition rather than a desperate fire sale.

But there was one problem: our debt financing partner. Our new acquirers needed them to take a haircut on the outstanding loans, but the lender had other ideas. They wanted every penny of what they were owed, and they wanted it now. The negotiations turned into a three-way standoff: us hoping for any deal, the buyer wanting a discount, and our debt financing partner refusing to budge.

In May, one of our advisors wrote the email that summed up our position: “Accept anything higher than 0”. That’s where we were - grateful for literally any amount of money. But even that was too optimistic. In June, the buyer walked away. After six months of negotiations, due diligence, and false hope, they walked away. The debt financing partner wouldn’t negotiate, so there was no deal. We’d kept the company on life support for half a year for nothing.

With the acquisition deal dead, we had one option left: bankruptcy. The Swiss subsidiary, Koj AG, would be formally wound down in a bankruptcy court. The furniture contracts would be… well, we weren’t sure what would happen to them. The debt financing partner could theoretically try to collect on the loans, but the furniture was already in customers’ homes across Switzerland and Germany so that wouldn’t be easy.

Carlo and I sat on a Zoom call - we were always on Zoom calls - and did the math. We had about $700,000 left in the US entity. Our burn rate was down to $30-40k per month. If we were careful, we had maybe 18-24 months of runway. Enough time to try something else.

The logistics of shutting down a furniture business are absurd. We had customers with active subscriptions who needed support. Furniture that needed to be reclaimed from churned customers. A storage unit in Zurich filling up with returned sofas. Carlo arranged for our delivery partner to do pickups while I created spreadsheets tracking which customers owed what, knowing we’d likely never collect.

The final insult came when we tried to calculate what the debt financing partner could actually recover. I pulled the data: over a mil in furniture at purchase price, theoretically worth more than $2 million at retail. Except it was scattered across 200 apartments in two countries, some of it damaged, most of it now “used”. Even if they somehow repossessed everything, they’d be lucky to get 20 cents on the dollar. Everyone lost.

By July, it was over. Koj AG entered formal bankruptcy. A process that finally completed after two years. While lawyers handled the liquidation paperwork, I wrote a post-mortem. Not the sanitized version, the real one - the one that admitted we’d been losing money on every single apartment for months and didn’t know it, the one that acknowledged we’d prioritized growth metrics over unit economics because the charts looked better, the one that said we should have killed this thing six months earlier.

Here’s what I wish I’d understood earlier: subscription furniture in Europe was fundamentally a zero interest rate phenomenon. When money was free, it made sense to finance $20,000 of furniture over four years. When interest rates hit 5%, the math stopped working. We could have seen this coming if we’d been watching the right indicators. Instead, we were watching MRR go up and to the right, not realizing each new sale was digging us deeper into a hole.

The recurring joke in our standups became “Today’s goal: Try not to die”. Some days, that was literally the only goal. Don’t run out of cash today. Don’t get sued today. Don’t have another vendor cut us off today. It’s amazing how clarifying imminent death can be for prioritization.

Finding the next thing

But here’s the thing about near-death experiences: they clarify what you actually want to do with your life. While the furniture business was in its death spiral, Neel, Carlo, and I started a Notion document titled “Pains and pivot ideas”. We wrote down every problem we’d encountered over the past years - some directly from the furniture business, others completely out there. Each pain point got a potential solution, and by the end we had nearly 40 ideas.

Some were obvious derivatives of what we’d built. We knew how painful it was to input product data into our ERP system - maybe we could build a global product database for the furniture industry. We’d watched customers struggle with curtains and window treatments - maybe a fully digitalized curtain service. Could Pabio itself pivot to focus purely on the design service with third-party furniture integration?

Others came from our own frustrations as founders. Carlo couldn’t properly assess my technical skills when we first met - maybe we could build outsourced engineering interviews. Every company we knew struggled with outbound sales - maybe we could build “Facebook Ads for outbound”, an AI-assisted service that discovers leads and sends personalized emails. Could we sell our own internal ERP called Lounge as a product for subscription commerce businesses?

And some ideas were truly out there. A job board specifically for ex-founders who didn’t want typical 9-to-5 jobs, which could have been us in the near future. A subscription service for MacBooks, basically Pabio for laptops. A fully digital migration service because both Carlo and I know what a nightmare it is to move to a new country. Or a personalized supplement subscription because Carlo was deep into longevity research?

Three ideas rose to the top: an ERP for subscription services (basically Lounge as a product), a unified database of all physical product data (solving the nightmare of inputting furniture specs called Produit), and an AI outbound tool called FirstQuadrant (we move your sales graph up and to the right). We did dozens of customer interviews for each, talking to anyone who’d give us an hour of their time.

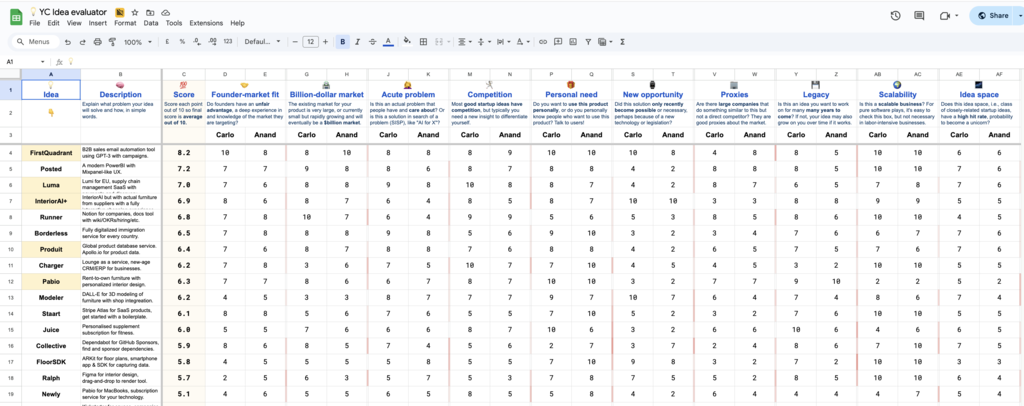

I used Y Combinator’s ways to decide what’s a good startup idea and created a spreadsheet to score them. Each idea got scored on ten criteria: founder-market fit (did we have unfair knowledge of this market?), billion-dollar market potential, how acute the problem was, competition levels, personal need (did we want this product ourselves?), whether it was a new opportunity enabled by recent technology, existence of successful proxies, legacy potential (would it compound over time?), scalability, and idea space (were there adjacent opportunities?). Carlo and I scored each independently, then averaged.

FirstQuadrant came out on top with an 8.2. Every founder we talked to had the same complaint: outbound sales was either impossibly expensive (hire SDRs) or impossibly time-consuming (do it yourself). The pain was universal and urgent. OpenAI had launched text‑davinci‑002 (an updated GPT-3 that actually worked well) back in March 2022 - Carlo and I had found it interesting, but not worth distracting from our existing business yet. Now, with Pabio dying, we had the perfect excuse to dive in.

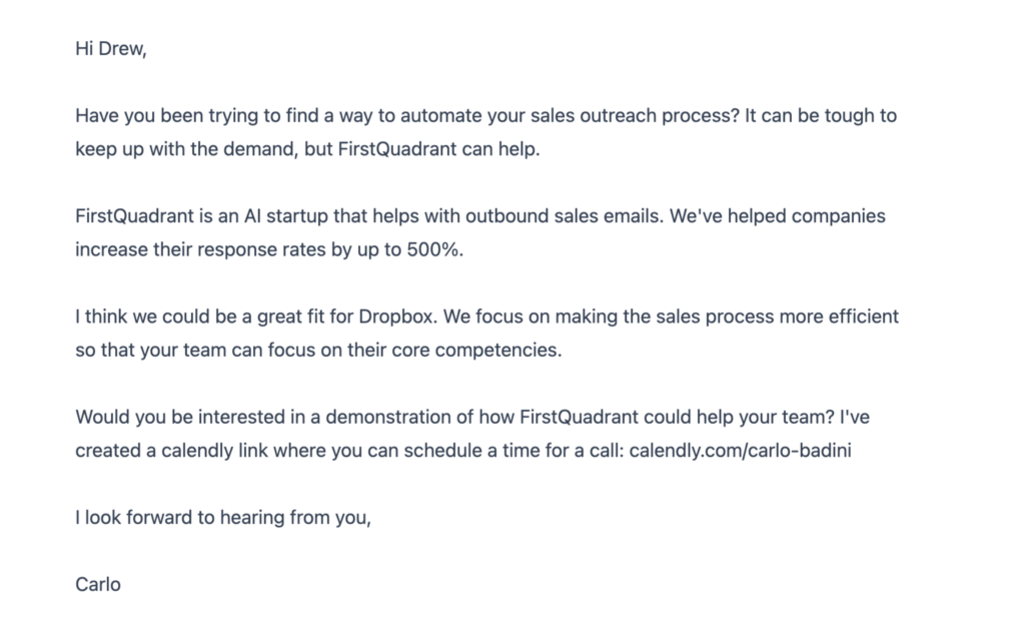

On October 22, 2022, I built a prototype called Project Autopilot. I hacked it together in about two hours by combining the Clearbit API for enrichment with the OpenAI API for generation. You entered sender details and a recipient email, clicked “Generate email copy”, and got a personalized pitch. The proof of concept worked well enough that we showed it to our friend and investor Jeremias Meier. A week later, on October 29, Carlo suggested the name FirstQuadrant - “we make sure you move your company up and to the right.”

We went deep. We studied how these language models were trained, how they worked under the hood, what their limitations were. ChatGPT launched on November 30 and suddenly everyone was talking about AI - but we’d been experimenting for over a month already. We ran unit economics based on GPT-3’s pricing at the time - could we actually make money sending AI-generated emails at scale? The answer was yes, barely, if we were clever about it. We ran dozens of experiments: Could GPT-3 write a cold email that didn’t sound like spam? Could it personalize at scale? Could it respond to replies naturally?

The results were promising enough that by January 2023, we’d launched the prototype of FirstQuadrant - in the same week that I got married to Sukriti - but that’s a story for the next article. While negotiating with the debt financing partner in the morning, we were testing GPT-3 prompts in the afternoon. While canceling furniture subscriptions, we were sketching product mockups in Figma. The furniture was dying, but the company - whatever it was becoming - was still alive.

Three takeaways

Here are the three most important lessons I learned from Pabio’s collapse:

Financial reality doesn’t care about your YC badge.

We discovered we were losing money on every order after months of bleeding cash, all because we didn’t have proper financial controls. Not having a real-time view into unit economics when you’re managing debt financing, inventory, and multi-currency operations is reckless not lean. We had gorgeous-looking MRR charts while hemorrhaging money on every sale. Every startup thinks metrics dashboards equal financial understanding. Plot twist: you can’t pay salaries with vanity metrics.

External dependencies are existential risks.

Our entire business model depended on a debt financing partner continuing to fund furniture purchases. We had no Plan B, no alternative funding sources lined up, no way to operate without them. When they pulled out, we had 72 hours to invent a new business model. Every critical dependency you can’t control is a ticking time bomb. We learned that “asset-light” can quickly become “asset-impossible” when your financing partner ghosts you.

Wind-downs are harder than startups.

Starting a company is exciting - everything is potential and promise. Shutting one down is a slow grind through legal documents, angry customers, and disappointed stakeholders. It took us eight months to properly close Pabio, and we’re still occasionally getting emails about furniture warranties. We learned that the same optimism that helps you start a company makes it almost impossible to know when to stop. The sunk cost fallacy is more than an economic concept; it’s an emotional reality when you’ve spent years building something. The only thing that made it bearable was having something new to build - testing GPT-3 prompts while canceling furniture subscriptions kept us sane.

Next up: How we went from selling sofas to selling software in 48 hours, and why building an AI SDR even before ChatGPT launched was simultaneously the best and worst decision we could have made: Building the first AI SDR (coming soon).