The Life of Pabio

This is the second chapter in my five-year retrospective. After accidentally founding Koj, we somehow convinced Y Combinator to let a furniture company into their batch (I still don’t know how) and embarked on what I can only describe as the wildest operational rollercoaster of my life.

Convincing Silicon Valley that sofas are SaaS

We weren’t building the next frontier AI model or developer tool, we were arguing about ottoman colors and delivery windows, so it was a bit of a stretch. But YC had been my dream since high school computer club, and Carlo was also game - but only if we didn’t have to abandon our customers in Switzerland. Carlo and Neel were showing up to every single delivery back then, sometimes even helping the delivery guys physically carry things up apartment stairs. Try explaining that in a YC application: “Our competitive moat? We personally ensure your furniture doesn’t get stuck in the stairwell.”

We decided that we’d only apply if we can attend remotely, and because of pandemic season the Summer 2021 batch was so. Carlo’s childhood friend Raphael, who’d done YC with Cron (later acquired by Notion), gave us a recommendation and ran us through mock interviews. We spent an entire weekend perfecting our application, and recorded our video on Zoom - Carlo in Switzerland, me with my family in India, both trying to look like we knew what we were doing.

The wild part? Carlo and I had still never shaken hands, yet we’d somehow furnished 5 actual apartments. Our entire partnership existed in Slack and Zoom, but hey, we had 150 leads waiting and a deal with a company willing to finance them. My favorite part of our application was an answer Carlo wrote: “When selling Koj subscriptions, it’s fascinating how little people understand present value. A customer will say $350/month for 3 years is outrageous, then happily sign for $300/month for 4 years.” We’d discovered that people hate math as much as assembling IKEA furniture.

Some time later, our inbox pinged: interview invite. We’d just gone from a 2.5% chance to about 25% (we heard that YC interviews 4x as many companies as they fund), and now we had a real shot. We prepared hard, maybe a bit too hard.

The YC interview is extremely information-dense because you go through so much in only ten minutes. I don’t even remember what we talked about; I just remember feeling like we’re not going to make it when it was over. It was late at night in Europe when the email came: “We’re on the fence. Can you do another interview in a few hours?”

We chugged coffee and jumped back on Zoom. This time, different partners, and somehow we were less terrified. Maybe it was the exhaustion, maybe it was the caffeine, but we actually sounded like we knew what we were doing. The next morning, Carlo’s phone rang. Michael Seibel on the other end saying “You’re in”.

Of course, the celebration didn’t last long before reality hit. Our internal processes were held together by duct tape, customers were DMing us about late deliveries, and we were still calculating prices in a spreadsheet. And now we had to do YC remotely, across time zones, while selling actual furniture.

Those first weeks were absolutely crazy. We’d be on YC dinners late at night in Europe, well past midnight in India, with one ear on the speaker and one eye on Slack where someone was inevitably asking why their dining table had three legs. I think these few months were the hardest I’ve ever worked in my life.

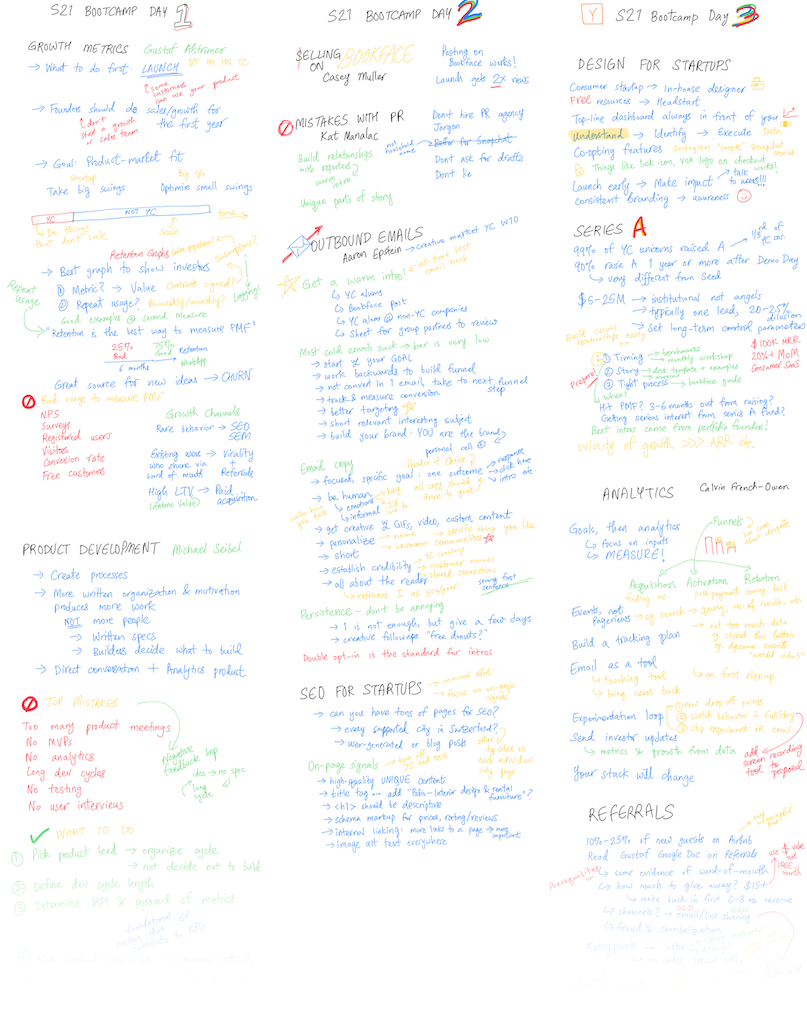

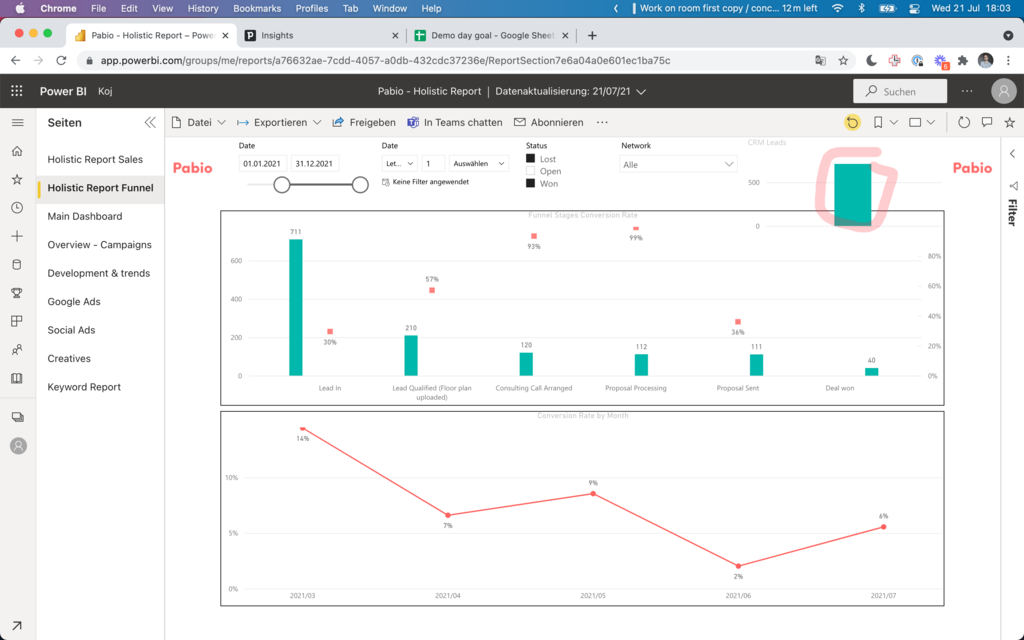

Here’s where we got creative (read: stupid). We invented MoKs - “Months of Koj” and used it as our key metric. As in, “How many MoKs did you sell this week?” to focus on longer contracts. Michael took one look at our weekly update and just asked, “What the hell is a MoK?” Turns out, when you invent your own metric, nobody knows if you’re doing well or terribly. Who knew? We switched to boring old MRR halfway through the batch, and suddenly our graphs started making sense to people who weren’t us.

The batch dynamics were fun too. Everyone else: “We’re building AI for developers!” Us: “We’re trying to figure out if this sofa will fit in a Swiss freight elevator.” But the YC partners got it. They’d seen Airbnb deal with actual physical spaces and DoorDash handle actual food.

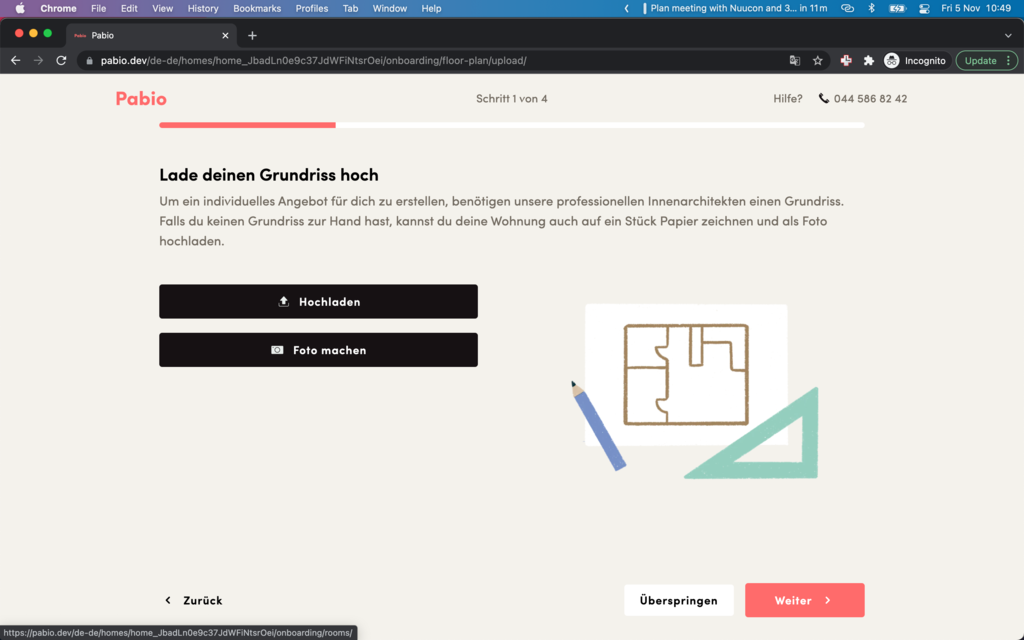

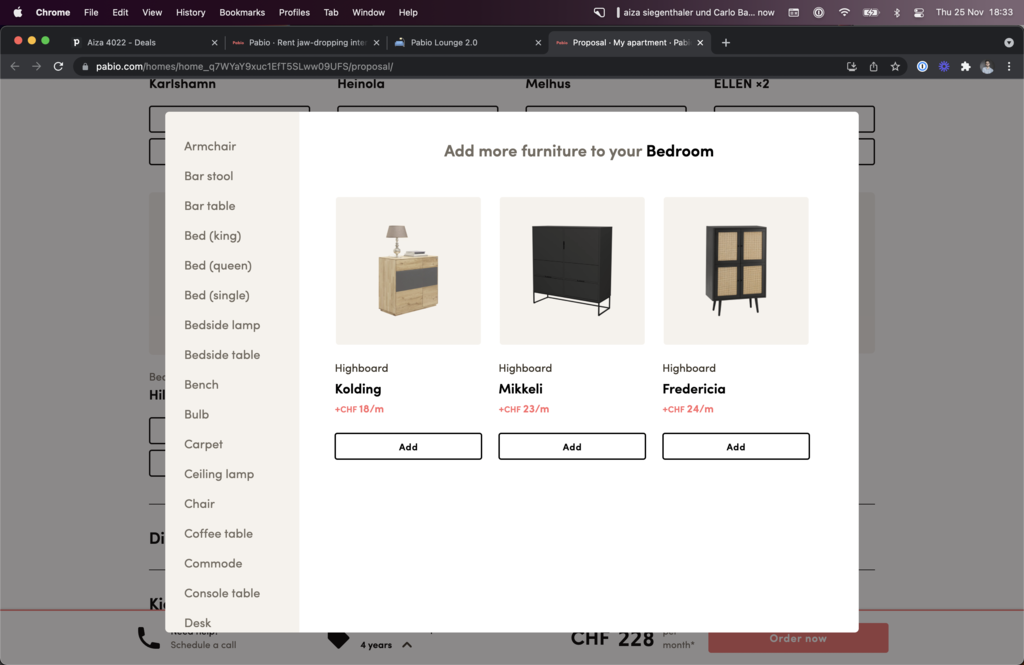

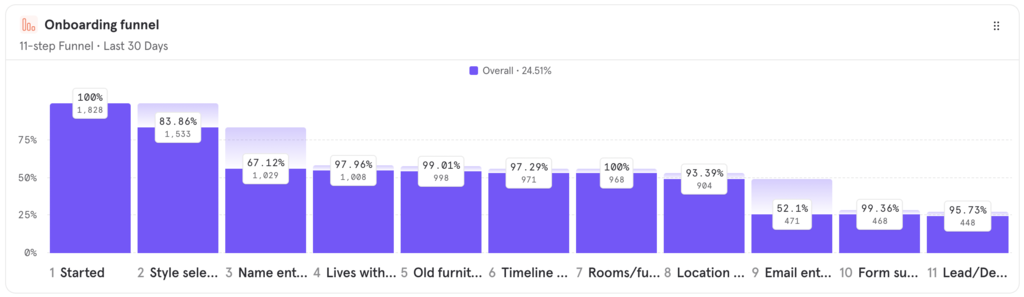

The batch program forced brutal prioritization. We had to choose between fixing our broken onboarding flow (losing 75% of paid leads between signup and form completion) or expanding to Germany, a much larger market. Between automating our painful manual ordering process or adding the self-serve checkout, the answer was always “fix the thing that’s killing you today.”

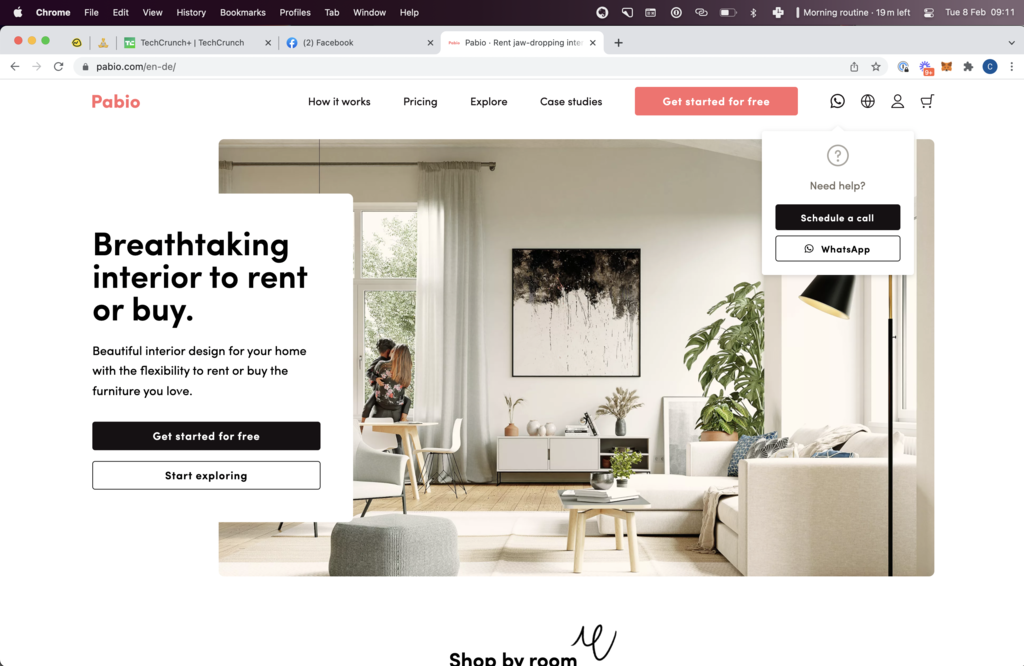

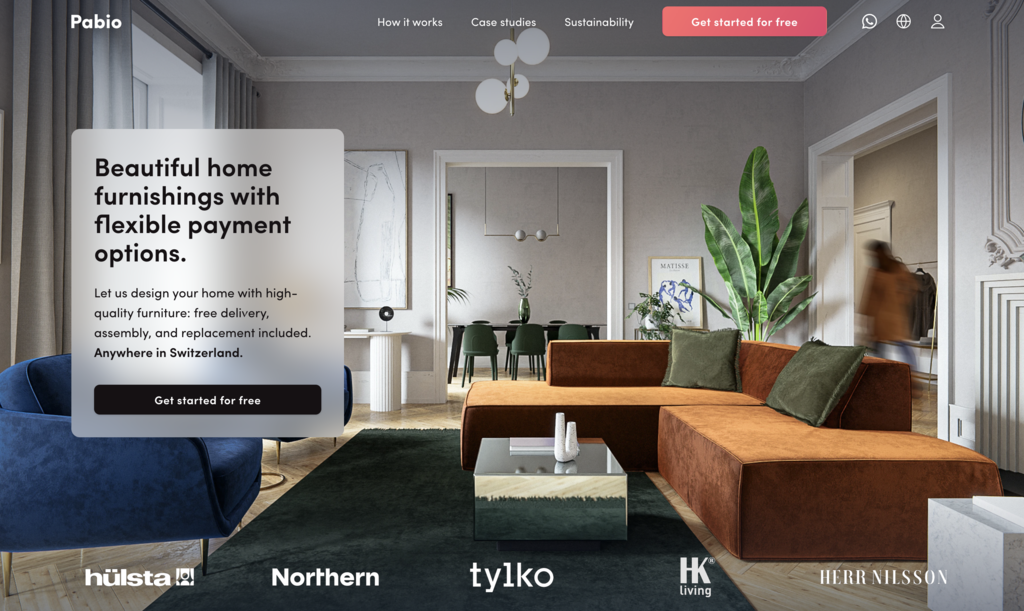

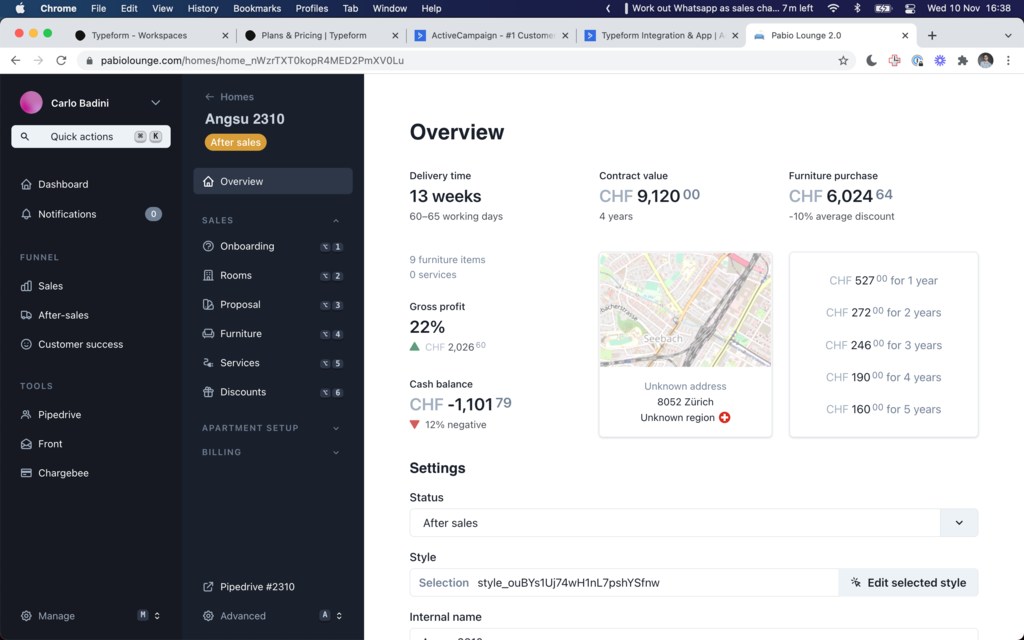

By August, Demo Day prep consumed everything. We practiced our pitch several times, iterating between “We live in a subscription economy, so we’re doing that for furniture” (too abstract) and “We’re digitizing Europe’s €50 billion furniture rental market” (too boring). We finally landed on a simple story: young Europeans move frequently, can’t afford tens of thousands to furnish apartments, so we give them designer homes for €300/month.

In fact, your company blurb (short intro) is something YC helps you write on day one, and you keep refining it throughout the batch; our final version was:

Pabio offers personalized interior design with high-quality furniture rental for Europe. With our asset-light rent-to-own business model, qualified customers can get $20k of new furniture with $0 upfront and monthly payments for up to 4 years.

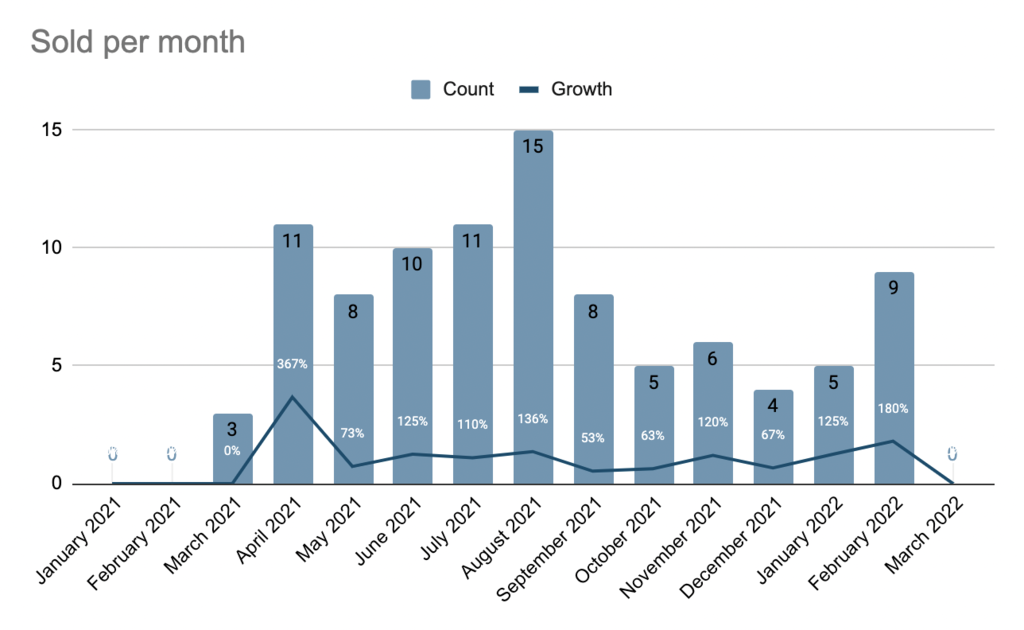

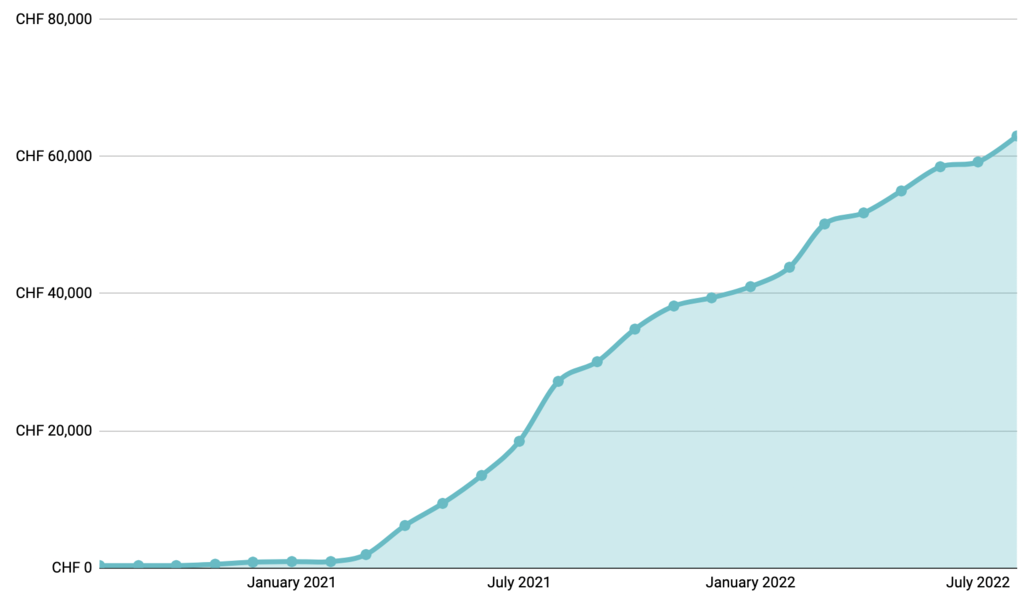

Demo Day itself was relatively anticlimactic because it was on Zoom instead of the live performance you’d expect, but we were already over halfway done with our seed round by then (many investors reach out to you during the batch). We had grown from $10K MRR to around $30K MRR in those three months, so we wanted to raise $2M at a $20M cap. We ending up putting a hard stop at $2.2M at $25M, mostly over Zoom calls, bringing our total funding to almost $3.5M.

People always ask: “Was YC worth it?”

Well, for one, we went from being “those furniture guys” to “those YC furniture guys.” That orange logo is basically a cheat code for fundraising. Investors who passed pre-YC at a $10M valuation for being too high were suddenly sliding into our DMs at a $25M valuation. The same pitch, the same team, the same questionable unit economics - but now with YC prestige.

But honestly, the real value wasn’t the badge (though the badge was nice). It was learning from partners who’d seen every possible way a startup could fail and somehow still believed in us. It was batchmates who became actual friends, not just LinkedIn connections. It was discovering that even successful founders feel like they’re winging it most of the time. It’s being part of a team for life.

And we had to “flip” our Swiss company to Delaware because American investors are allergic to foreign entities. We kept the Swiss company as a subsidiary, which seemed annoying at the time but turned out to be genius when we pivoted - all the furniture liabilities stayed in Switzerland while the US entity stayed clean. Sometimes it’s better to be lucky than smart, and we were definitely more of the former than the latter.

Scaling chaos

Post-YC, we had millions in the bank and thought we’d finally escaped startup chaos (nope). Instead, every week brought a new flavor of disaster. Here’s the greatest hits album from our first few months as real startup with real startup money:

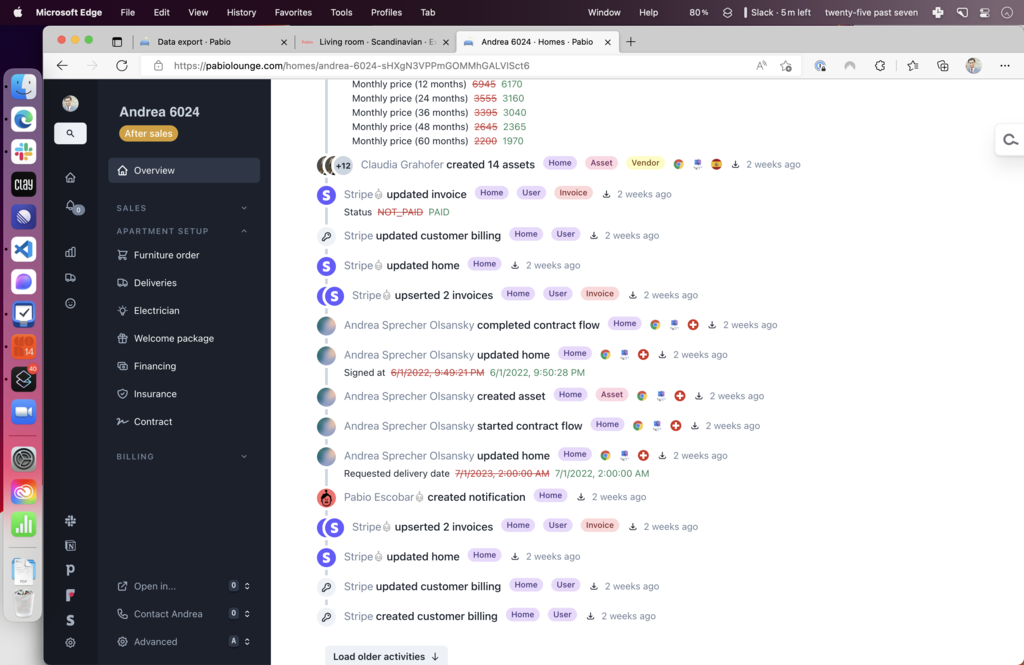

The great payment migration of 2021: We’d built our entire billing system on Chargebee. Turns out, their SDK was riddled with bugs. We were spending more time debugging their API versions than actually charging people. We decided to migrate to Stripe, and I sent a Slack message that went something like: “Nobody touch ANYTHING payment-related until midnight. I’m not joking. Don’t even LOOK at the payments dashboard. Don’t even THINK about payments. Pretend money doesn’t exist.”

The migration was a nightmare of edge cases. Some customers had been double-charged due to duplicate subscriptions. Others had contracts but no payment methods. We discovered over $40K in unpaid invoices that Chargebee simply hadn’t been collecting. Monique, our (external) finance lead, was working overtime to reconcile accounts while I wrote scripts to sync data between three different systems.

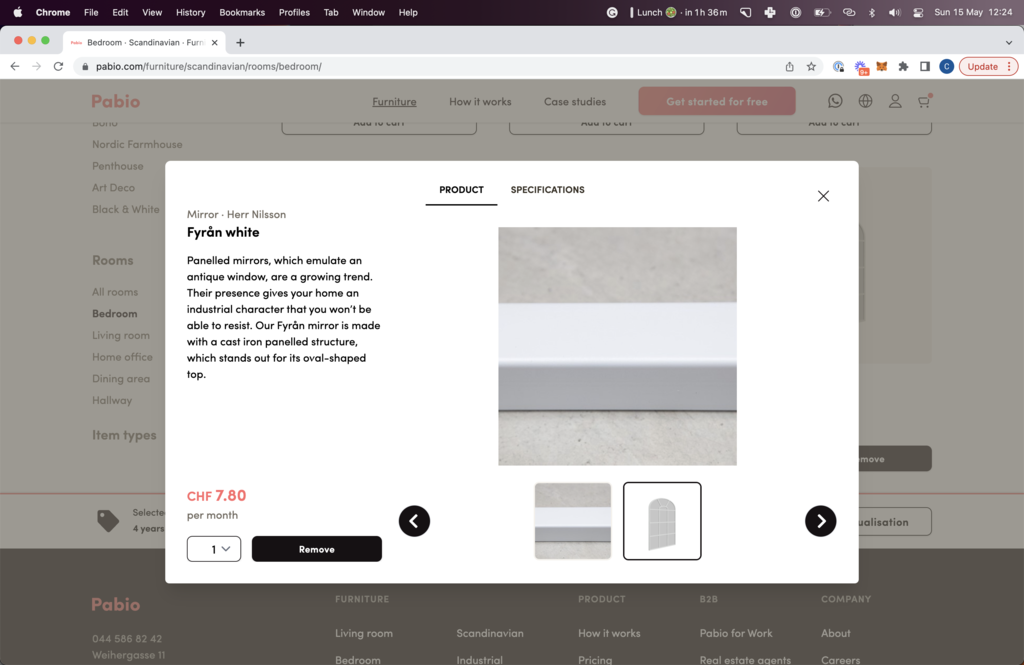

The render revolution: Remember when customers would say “I love it, but can you switch to the blue armchait?” and we’d die a little inside because that meant 48 hours of re-rendering? Yeah, that was sustainable for exactly zero seconds at scale.

Ralph, our 3D wizard, had this crazy idea: “What if designers could just drag and drop furniture?” Six weeks of caffeine-fueled coding later, we had a visual builder that could generate renders almost in real time. Our AWS bill was high with all those GPUs running at full blast, but watching designers drag a sofa onto a floor plan and get a photorealistic render in minutes? Pure magic.

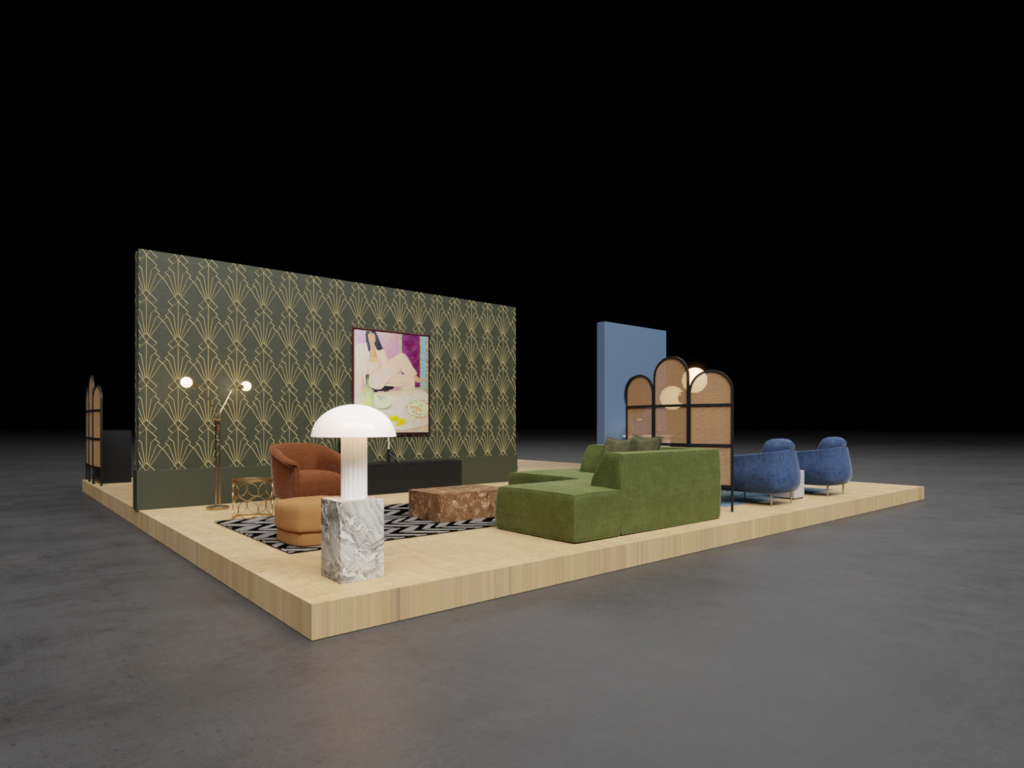

But the real breakthrough was the render pipeline itself. Raphael and Laura, our 3D artists, created a library of thousands of furniture models. We standardized everything: 1920x1300 resolution, consistent lighting angles, realistic material textures. When customers saw our renders, indistinguishable from photographs of their apartment, they were ready to sign up for a subscription.

The German expansion: “How different can Germany be?” we asked ourselves. “It’s literally next door!” Oh, sweet summer children.

Turns out Germans have this thing called “Rechnung” where they want to receive an invoice, think about it for 30 days, maybe pay it, maybe not. The Swiss credit system (CRIF) didn’t work in Germany (SCHUFA). VAT rules were different, payment preferences were different, even the way people measured their apartments was different. Especially because we had to ship the furniture from Switzerland to Germany and deal with border taxes and customs.

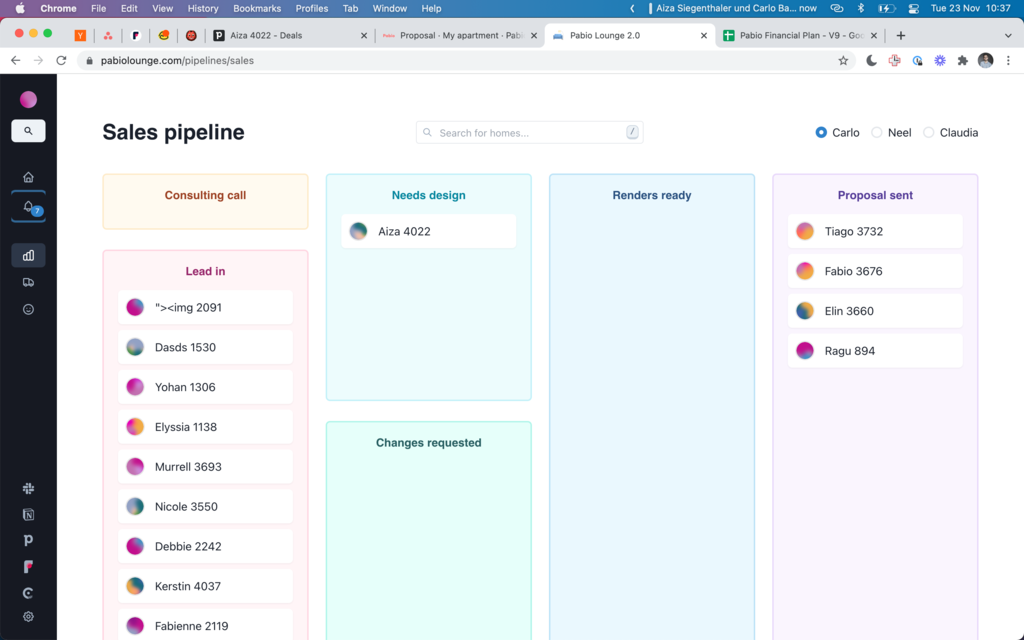

Our “copy-paste Switzerland to Germany” strategy didn’t last long. We hired Claudia, a veteran from big furniture companies, who took one look at our operations and probably wondered what she’d gotten herself into. She became our COO and our collective sanity, starting with setting up deals with more furniture suppliers.

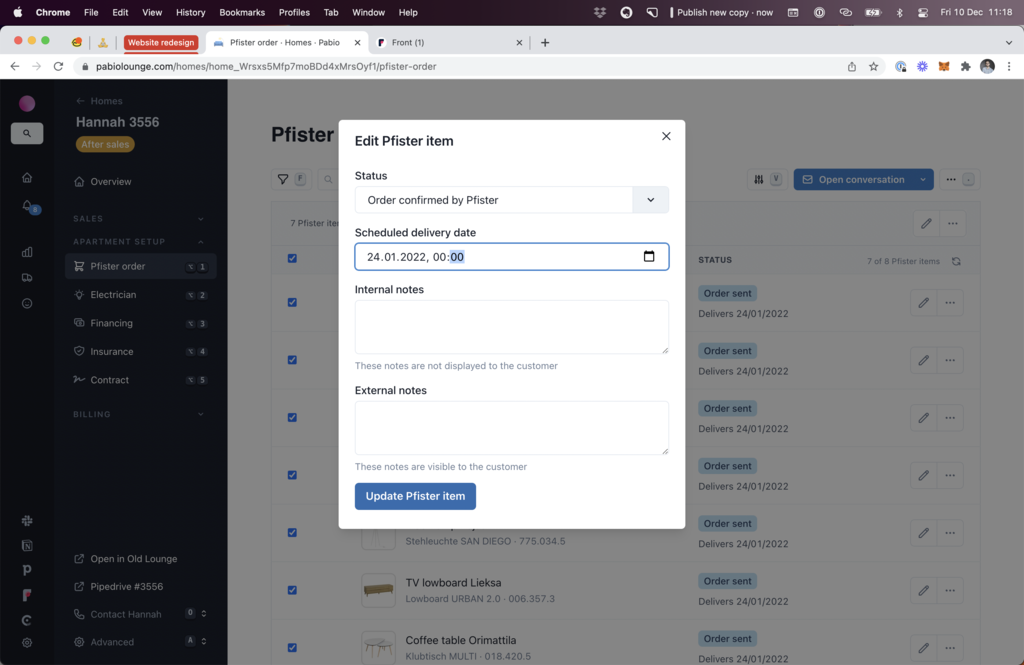

The supplier situation was a beautiful disaster. Pfister gave us great prices but had 16-week lead times. One supplier only accepted orders via email, another had a B2B portal that worked exclusively on Internet Explorer, and my personal favorite - a supplier who insisted we call them to confirm every email we sent them.

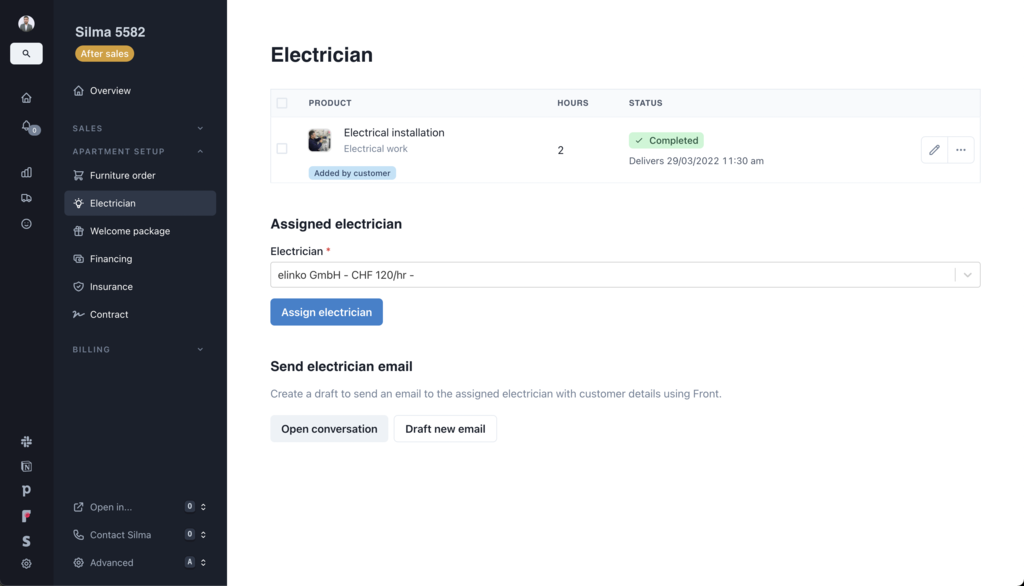

I always thought I would be brainstorming solutions to JavaScript bugs and not to “oh no, the supplier forgot to ship legs with the dining table”.

Marketing addiction: We started innocently enough. Just a few A/B tests. Maybe a new headline here, a button color there. Before we knew it, we were spending thousands every week on Facebook and Google. Our CAC was over $2,000, but we had a great rationalization: “It’s fine! They sign 3-year contracts!” (Narrator: They did not all keep their 3-year contracts.)

We tried everything else. Word-of-mouth? People move apartments once every few years, not exactly something you can call your friends about. B2B partnerships? Real estate companies wanted kickbacks that would make our already questionable unit economics actually negative. Influencer marketing? Turns out nobody wants to watch a 20-minute Instagram story about someone’s rental couch. Shocking.

But like moths to a very expensive flame, we kept going back to paid ads. Every Monday: “This week we’re going to try and reduce paid spend.” Every Friday: “Okay, but if we just increase the budget a little, we can hit our target.” We were basically paying people to pretend our product had product-market fit.

Automation and Lounge

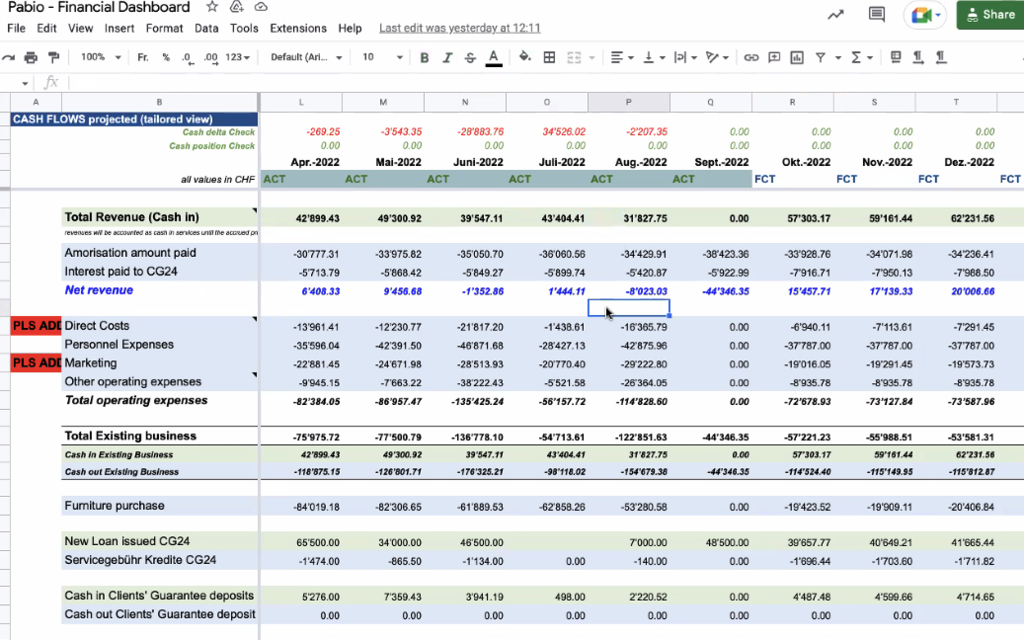

By early 2022, our operation were not operational. Picture this daily ritual: Check 15 supplier websites, calculate delivery windows using a spreadsheet, manually type the same order into six different systems (each with its own special way of formatting addresses), then track everything through an email thread.

Oh, and coordinate with logistics partners who communicated exclusively in German abbreviations I’m 90% sure they made up, plus electricians who had their own scheduling system that appeared to be based on lunar cycles. We knew something had to change. So we built web scrapers with the confidence of people who’d never built web scrapers before. “How hard can it be?” we asked. The #automation-errors Slack channel answered that question hourly.

My personal favorite disaster: One morning, half our catalog showed CHF 0 prices because a scraper decided to take a vacation without telling anyone. We woke up to emails asking if we were doing a “free furniture Friday” promotion.

Every “solution” created new problems. Scrapers worked! Until websites changed their HTML. We added Browserless! Until we hit rate limits and they thought we were DDoSing them. We tried Playwright! Until it ate so much RAM that our server just gave up on life. Finally, in a moment of exhausted clarity, we implemented the “good enough” rule: If a price changed by more than 50%, a human had to check it. Our prices became “roughly correct,” which was somehow an improvement. We updated everything at 3 AM when nobody was watching, like furniture elves, but significantly less magical.

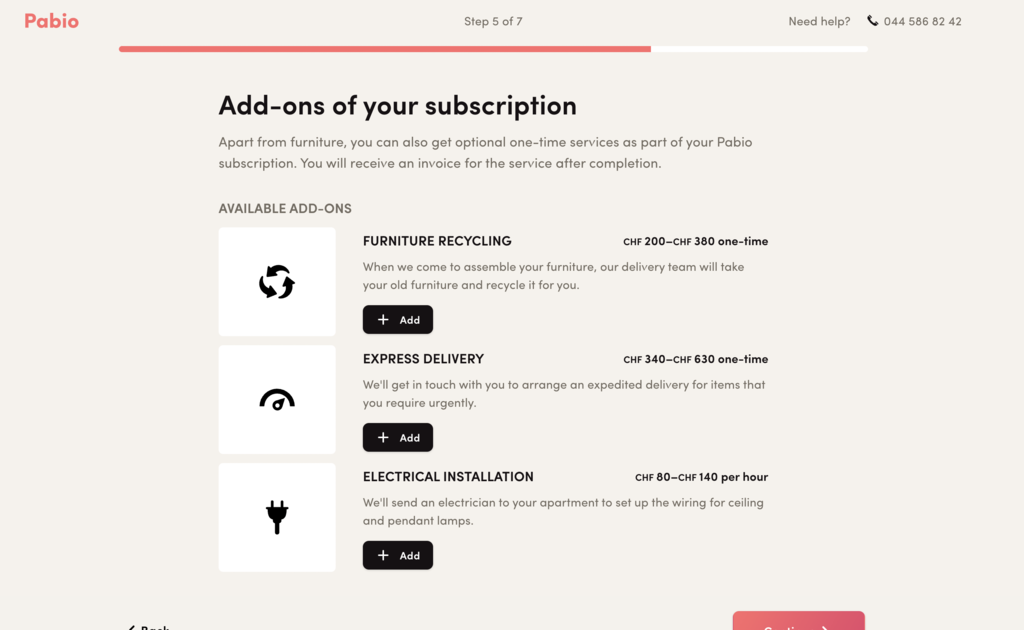

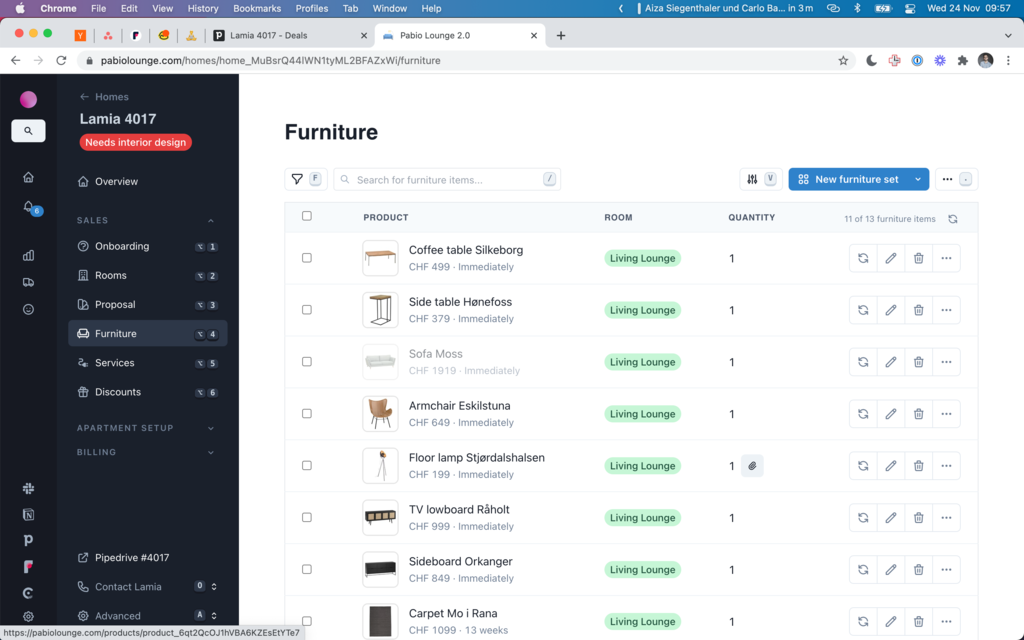

Then we built Lounge 2.0, because apparently we enjoy building ERPs from scratch. But honestly? It was beautiful. This Frankenstein’s monster of a system could do everything: upload floor plans, generate proposals, process e-signatures, place orders, coordinate deliveries, track installations, manage customer relationships, make coffee (okay, not the last one, but I would be lying if I said I didn’t consider it).

It was a CRM! It was an ERP! It was a design tool! It was whatever we needed it to be at 2 am when something broke! We were so proud of this thing. It was like our baby, if your baby was made of TypeScript and had a tendency to throw tantrums at the worst possible moments.

Building Lounge was probably my favorite mistake. Every startup founder has that one feature they built because they could, not because they should. Lounge was mine. We convinced ourselves we were “too unique” for off-the-shelf solutions.

The feature creep was legendary. We built an insurance integration for German customers, then we sold less than 20 apartments in Berlin. We created a pricing calculator for apartments, then we switched to simple per-product pricing. The automated invoicing system took hundreds of hours to build. It would have taken maybe 20 hours to manually create invoices for our first 100 customers. We could have just duct-taped Retool to Salesforce and called it a day. But no, we had to be “real” engineers building “real” systems.

From burnout in Istanbul to living in a train station

Our solution to every problem was magnificently wrong: add more options! Customer hesitant? New style! Conversion dropping? Another style! Random Tuesday? Why not add Boho Chic? Each style meant new SKUs, inventory management, and supplier relationships. We had more furniture combinations than entire stores, except we were 12 people operating out of our bedrooms.

We didn’t add these styles for no reason, it was because customers were asking for something “different”. Turns out they weren’t asking for more options, they were trying to politely ghost us. We were the furniture equivalent of “it’s not you, it’s me” and we just kept offering more date ideas.

We became the “yes” company. Special cancellation terms, net-60 payment, outside our service area? we’ll figure it out! Each “yes” created what I call operational debt - future pain we were borrowing against current revenue. When our biggest customer churned, it was $10K MRR gone - poof. The special cancellation clause we’d agreed to meant they could leave whenever they wanted with zero penalty. Only much later did we make a hard rule, “no weird deals”.

Our feature factory went into overdrive too. Add virtual consultations, per-room planning service, style quiz, referral program… we were like a restaurant that keeps adding dishes to the menu instead of asking why nobody wants to eat there.

The funny thing? Our MRR graph looked great. Up and to the right! We were basically running a very expensive charity for people who wanted nice furniture. Except charities usually know they’re charities.

By May 2022, we were all pretty much deserving a mental health day. Our Slack had devolved into a stream of fire emojis and crying-laughing faces (heavy on the crying), so we decided to take a week off in Istanbul. Neel turned into a travel agent overnight, coordinating plans from Zurich, Berlin, New Delhi, and Groningen. We descended on Istanbul like a very confused, slightly exhausted United Nations of furniture.

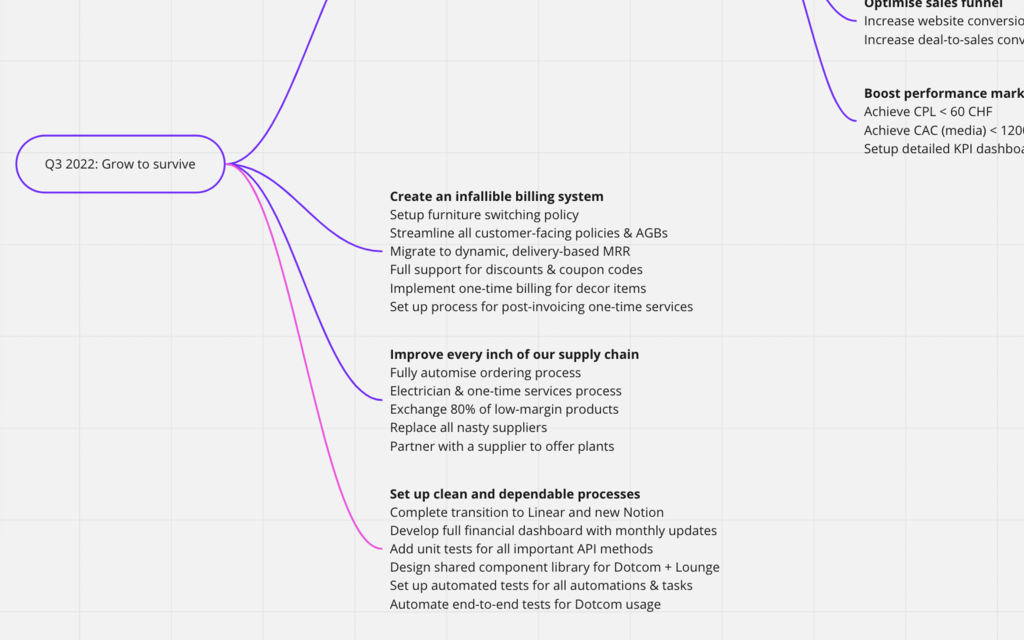

We spent a week in this beautiful city, alternating between intense whiteboarding sessions and fun activities. By day three, we’d actually agreed on priorities. By day five, we had OKRs that made sense. By day seven, we felt like an actual team again instead of people accidentally building the same company.

Later, Carlo suggested the idea that was either genius or insane (still not sure): “What if we build an apartment in Zurich’s main train station?” Not a booth, not a display, an actual, functioning apartment in the middle of Switzerland’s busiest train station. Where Carlo would actually live for the better part of a week.

The planning was absurd. You ever try to get permits to build a bedroom in a train station? The Swiss paperwork alone could have furnished a small apartment. We had to coordinate interior design, furniture delivery, electrical installation, and somehow convince the authorities that yes, a CEO sleeping in a train station was a legitimate business strategy.

But we did it. We built a gorgeous apartment with no walls, right there between the takeaway stands and the departure boards. Complete with a bed, dining table, designer lighting, and a very confused Carlo trying to act natural while 50,000 commuters walked by daily.

We hosted different groups for dinner each night: customers, investors, friends. I became a sushi procurement specialist (shoutout to the station’s takeout place and Uber Eats for sponsoring) and resident dishwasher.

Because I have no boundaries, I set up a 24/7 live stream. People could literally watch Carlo sleep. The internet is weird, and apparently, people will watch anything, because we had hundreds of viewers at 3 am watching our CEO snore in a train station.

This was our peak. Not in revenue, not in metrics, but in pure startup audacity. We’d convinced Switzerland’s’ busiest train station to let us build a bedroom in their train infrastructure. We got Swiss people to stop and chat (a miracle).

For five glorious days, Zurich HB was Switzerland’s most unusual furniture showroom. Thousands of people stopped by, from curious teenagers to working professionals asking if we could furnish their homes. We collected hundreds of leads, though I suspect some just wanted to see if Carlo was really sleeping there (he was).

The real win wasn’t the leads or even the press coverage. It was proving that we could pull off something absolutely bonkers and make it work. If we could build an apartment in a train station, surely we could figure out unit economics, right? (Narrator: They could not figure out unit economics.)

But for those five days, surrounded by the chaos of Switzerland’s busiest train station, eating station sushi at a designer dining table, watching Carlo explain subscription furniture to bemused commuters - we felt like we were exactly where we were supposed to be. Even if that place was, admittedly, very weird. We had made it. But not for long.

Three takeaways

Here are the three most important lessons I learned from the life of Pabio:

If you need to constantly buy customers, you don’t have product-market fit.

Our addiction to paid acquisition was a symptom, not a solution. We were paying people to want our product rather than fixing why they didn’t want it organically. Real product-market fit doesn’t require a marketing budget to sustain. If you don’t have word of mouth, referrals, and organic growth on day 1, you likely won’t have it on day 1,000 either.

Don’t reinvent the wheel for the sake of it.

When we picked MoKs instead of MRR, we thought we were being clever, but we were just being confusing. Standard metrics create alignment, enable comparison, and prevent self-deception. And Building Lounge before we knew what we actually needed was classic premature optimization when we could have used existing tools. Every time we ignored peer-reviewed, empirically-proven advice like YC’s, they were right and we were wrong.

Complexity is the enemy of growth.

Whenever we faced a growth challenge, our instinct was to add something new - more furniture styles, custom payment terms, bespoke contracts, virtual consultations. But each addition created exponential operational overhead. What started as flexibility to win customers became the very thing that made us too slow and expensive to serve them. The irony is that simplicity - one style, one price, one process - would have forced us to nail the fundamentals instead of papering over problems with complexity.

Next up: The story of how we discovered we were burning cash on every sale (math is hard), had an existential crisis on Zoom, and somehow convinced ourselves that pivoting from furniture to AI in 48 hours was totally reasonable. Spoiler alert: it actually worked (until it didn’t). Continue to the next article: Move fast and save things.